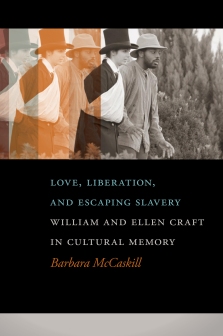

Barbara McCaskill is a professor of English and codirector of the Civil Rights Digital Library at the University of Georgia. She is the author of Love, Liberation, and Escaping Slavery: William and Ellen Craft in Cultural Memory and provided the introduction for the UGA Press’s edition of Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom: The Escape of William and Ellen Craft from Slavery. Ellen and William Craft are famous for how they escaped slavery in Georgia—Ellen disguised herself as a white male slave owner with William acting as her slave. They spent their years as freedpeople as activists. Below Barbara McCaskill elaborates on their story and why she started learning about it in the first place.

Barbara McCaskill is a professor of English and codirector of the Civil Rights Digital Library at the University of Georgia. She is the author of Love, Liberation, and Escaping Slavery: William and Ellen Craft in Cultural Memory and provided the introduction for the UGA Press’s edition of Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom: The Escape of William and Ellen Craft from Slavery. Ellen and William Craft are famous for how they escaped slavery in Georgia—Ellen disguised herself as a white male slave owner with William acting as her slave. They spent their years as freedpeople as activists. Below Barbara McCaskill elaborates on their story and why she started learning about it in the first place.

The story of William and Ellen Craft escaping slavery is both inspiring and fantastical in the way that Ellen disguised herself as a white slave owner. What first got you interested in their story? What is your favorite part of their ingenious escape?

The story of William and Ellen Craft escaping slavery is both inspiring and fantastical in the way that Ellen disguised herself as a white slave owner. What first got you interested in their story? What is your favorite part of their ingenious escape?

I became interested in the story of the Crafts because of two goals: to complete a book about women’s involvement in the development of American slave narratives, and to prepare for my position as an incoming professor at the University of Georgia. The Crafts’ story intersected with both of these goals, since Ellen participated in constructing their collaborative narrative and since both William and Ellen are natives of Georgia. My favorite part of their escape is actually their second flight from slavecatchers pursuing them in Boston, two years after they left Georgia in 1848. This second cat-and-mouse chase succeeded in the Crafts’ favor because of cooperation from an interracial coalition of antislavery activists, inclusive of women and men, and it involved a very lively and outspoken cast of characters.

In the time period that Ellen Craft (1826-1891) lived in, people adhered to very strict gender roles (i.e., women were supposed to be seen and not heard), and yet Ellen Craft is remembered for her activism. In what ways did Ellen Craft go against traditional patriarchal values to become an activist for not only African-Americans but also women?

Ellen accompanied her husband William to antislavery meetings in the US and England and appeared consistently with him on public stages, even though she largely remained silent because of gender expectations about respectable female behavior. This decision to cultivate a public presence visibly communicated that she was not willing to shrink into the shadows now that she was free. Necessity required Ellen to make inroads for women as a breadwinner and teacher as well as activist, particularly for African American women, since William was absent for long stretches of time as a merchant in West Africa and then to raise funds in New England for their Georgia education project.

After escaping slavery, the Crafts were forced to flee to England to escape slave hunters. When the Civil War ended they could return to the United States without fear of running into slave catchers. What was it like for the Crafts to no longer live with this fear?

After escaping slavery, the Crafts were forced to flee to England to escape slave hunters. When the Civil War ended they could return to the United States without fear of running into slave catchers. What was it like for the Crafts to no longer live with this fear?

Although the Crafts no longer feared slave catchers, when the Civil War ended and they returned to the United States they faced additional challenges. Slavery had ended but white supremacy had not. For example, as Reconstruction waned, night riders burned down one of their schools, and another school resulted in a lawsuit instigated by indignant white neighbors. After living in exile in England for nineteen years, and publishing two editions (in 1860 and 1861) of their memoir, the Crafts returned to the US very different people socially and culturally from the black southerners they returned to educate. They were challenged by the prospect of living in a country which stubbornly resisted extending full rights of citizenship to African Americans, which would unfurl segregationist policies that criminalized and disenfranchised African Americans, and which turned a blind eye to the increasing racial violence and domestic terrorism meant to disempower black people.

William and Ellen wrote their book Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom in 1860, 10 years before they returned to the United States. Though their return to Georgia was less harrowing than their escape, it is an equally important part of their story. Why was it so important for them to return to the U.S. at all?

The Crafts’ return to Georgia resulted from the convergence of many elements in the couple’s lives. Like most fugitives from American slavery in England and Europe, they had struggled to stay afloat financially, and they had lost their fine home in Hammersmith, London, to creditors. They both had attained an education, thanks to British benefactors. So they could contribute to the well-being and improvement of the freedpeople as teachers, in addition to sending their children, four sons and a daughter, to school. Finally, because they had left family members behind in slavery, both William and Ellen had spent their decades in England seeking to reunite with loved ones, to mixed results. By returning to the American South, they could continue to locate family members lost to the auction block. This latter desire was especially poignant, since the Crafts lost another infant daughter shortly after they returned to the US.

In what ways can the Craft’s story inspire activists today?

The Crafts’ story is one of numerous moments in what scholars call the long civil rights movement, African Americans’ struggle for equality and citizenship which has gone unbroken and unresolved since the first enslaved Africans were brought to North America’s shores centuries ago. What can inspire activists today is the Crafts’ resilience after setbacks, as well as their strategy of utilizing a variety of platforms simultaneously to communicate antislavery and antiracist goals: newspapers and books, public speeches and lectures, and visual iconography (i.e., the famous engraving of Ellen Crafts, disguised as an invalid southern planter). The Crafts’ rehearsed another activist strategy which is apparent in the March for Our Lives gun safety movement: to build coalitions across boundary lines of race, class, gender, region, education, and other differences in order to agitate effectively for social change.